Rarara - Reversing (Secuinside CTF)

This is a writeup of the challenge rarara from the secuinside 2014 pre-qual ctf.

I participated in this challenge together with Yoav Ben Shalom, Matan Mates, and Itamar Marom. This was the probably the hardest challenge in the competition and only one team had managed to solve it a few hours before the competition ended when my team had to leave early.

We had figured out the solution but ran out of time before implementing it. Had we stayed and finished this level and another we likely would have been in the top ten teams, but oh well!

The challenge

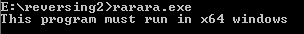

We were given a binary. You can download it from here. Running it from the command line yields

While the easy solution might be to install 64 bit windows, examining the assembly reveals that the code is actually 32 bit binary. I’m not sure why this check is done, but it’s easy enough to patch it (a single jz -> jnz) and allow the binary to run on 32 bit systems.

Next we are presented with a prompt asking for input. Trying a few random inputs, we get the message “Wrong!”. It’s time to open up IDA and see what this program does!

Anti-reversing

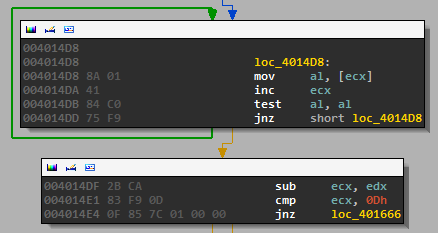

Once we’ve identified the important function, we can see a few things. First, the length of the input is checked and compared to 13.

Then each of the letters is checked to make sure it is alphanumeric

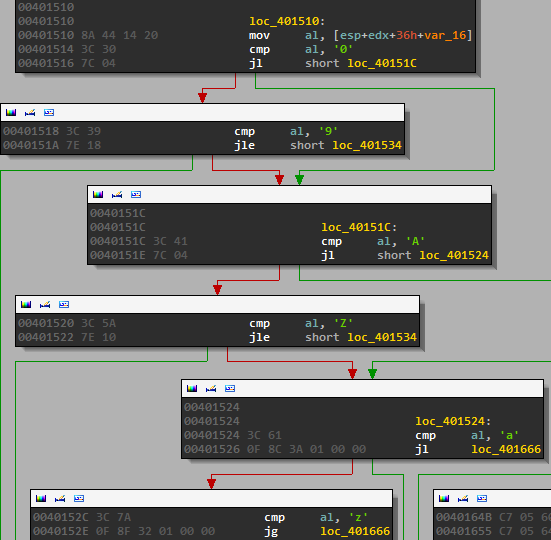

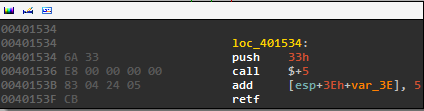

And then we reach this block at which point IDA’s analysis fails us:

This block is repeated in many different locations throughout the code.

What is this block doing? When we call $+5 it puts our address on the stack. 3E+var3E is 0x3E - 0x3E = 0, so the add instruction adds 5 to the address just placed on the stack. Finally, we return to that address, or just after the retf instruction.

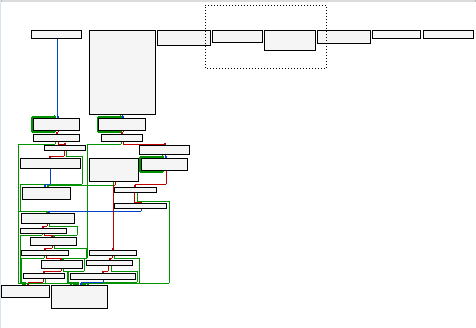

In other words, this whole block is just a compilicated nop that screws with IDA’s autoanalysis. By patching the binary to replace all instances of this block (plus some slight variations) with nops, we turn this:

into this:

So straight and organized! Now we can start working.

Understanding how the password is checked

After making sure that all of the characters are alphanumeric, the program places the letters into a global array in jumps of 0x14 while keeping track of the sum. The sum is later compared to 0x3E2 giving us our third constraint on the password (the other two being length and alphanumericness).

The global array is then processed in a loop. This was the third challenge in the competition involving CRC’s, so we quickly recognized the loop as calculating the crc64 of the global array (of length 0x100) with the letters of our password placed in the indexes as described above. The crc is then compared to a constant value.

If it is correct, then the value “Correct” is placed in the buffer where “Wrong” was held before so “Correct” will be printed at the end of the program.

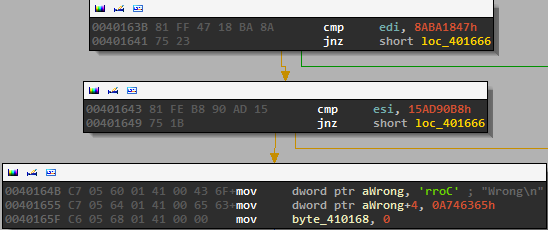

So, to summarize we need to find a password of length 13 comprised of alphanumeric characters whose sum is 0x3E2 and whose CRC64 when placed in a set array at specific indexes is equal to 0x15AD90B88ABA1847

Breaking CRC

A previous challenge involved appending data to the end of a string in order to obtain arbitrary CRCs. That’s a less helpful ability for this challenge since we’re not changing 8 consecutive bytes in the crc (so the same algorithm doesn’t apply) and there’s no way of ensuring we will only have alphanumeric characters.

However, there is an interesting property of CRC that we can use - CRC is a linear function. This means that CRC(x) ^ CRC(y) ^ CRC(z) = CRC(x^y^z). Since CRC(0) = 0 in this implementation (usually there is a xor with 0xxffff… that prevents this), we get CRC(x^y) = CRC(x) ^ CRC(y).

Using this knowledge, we can check how each bit of input affects the final CRC. We start by filling the array with a throwaway value - we filled the array with 0x41 (‘A’) as our base value. We then change a single bit and look at the new CRC. Since CRC(x ^ y) = CRC(x) ^ CRC(y) we get CRC(array with bit changed) = CRC(array) ^ CRC(effect of changing that bit)

In other words, we can look at what happens when we change a single bit and then figure out which bits we want to change and which we want to keep the same.

We do this by building up a matrix where each column is the effect of changing a single bit. By multiplying each row with the vector of whether or not we actually change each bit we should get the corresponding bit in the final CRC.

The problem then becomes one of solving a simple linear equation. Since we have 91 input bits (13 letters * 7 unknown bits since the upper bit is always 0) and 64 rows in our matrix (since the CRC is 64 bits long) we still need to iterate over 91 - 64 = 27 bits and check if the solution is valid (alphanumeric and proper sum).

We split our solution into two parts. First we generated a ranked matrix in python. We then found all of the solutions in C++ since our original python solution was too slow. You can see the code below.

Optimizations

The original C++ code was still very slow. It took around an hour to go over all of the possible values for 27 bits. The speed was significantly boosted by checking after every 7 bits if the letter was valid. This effectively allowed us to short circuit solutions that were known to be invalid and improved the speed to around 30 seconds.

The other major optimization was moving from vector<bool> to bitsets. Because bitsets have built in operator& and count functions that work effeciently the speed of the inner function was vastly improved (see below).

Using bitsets the speed of the program was reduced to 4 seconds.

But we can do even better :)

We know that the xor of the lower bits of all of the equations is zero, because the sum of the letters is even. Therefore, we can add a row to our matrix and we have one less bit that we have to brute force. Final speed is around 2 seconds.

Update: Even better

Michael Huzman pointed out that the builtin popcnt instruction should vastly improve the speed of the inner function. By adding the flag -march=corei7 gcc will automatically use this instruction for bitset’s count function. This again halves the speed and now it runs in 1.2 seconds!

Disassembly before and after:

Before:

0000000000401e80 <_Z5innerRKSt6bitsetILm91EES2_>:

401e80: 48 89 5c 24 e8 mov QWORD PTR [rsp-0x18],rbx

401e85: 48 89 6c 24 f0 mov QWORD PTR [rsp-0x10],rbp

401e8a: 48 89 fb mov rbx,rdi

401e8d: 4c 89 64 24 f8 mov QWORD PTR [rsp-0x8],r12

401e92: 48 83 ec 18 sub rsp,0x18

401e96: 48 8b 3f mov rdi,QWORD PTR [rdi]

401e99: 48 23 3e and rdi,QWORD PTR [rsi]

401e9c: 48 89 f5 mov rbp,rsi

401e9f: e8 bc ec ff ff call 400b60 <__popcountdi2@plt>

401ea4: 48 8b 7b 08 mov rdi,QWORD PTR [rbx+0x8]

401ea8: 48 23 7d 08 and rdi,QWORD PTR [rbp+0x8]

401eac: 41 89 c4 mov r12d,eax

401eaf: e8 ac ec ff ff call 400b60 <__popcountdi2@plt>

401eb4: 49 8d 04 04 lea rax,[r12+rax*1]

401eb8: 48 8b 1c 24 mov rbx,QWORD PTR [rsp]

401ebc: 48 8b 6c 24 08 mov rbp,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x8]

401ec1: 4c 8b 64 24 10 mov r12,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x10]

401ec6: 48 83 c4 18 add rsp,0x18

401eca: 83 e0 01 and eax,0x1

401ecd: c3 ret

401ece: 66 90 xchg ax,ax

After:

0000000000401df0 <_Z5innerRKSt6bitsetILm91EES2_>:

401df0: 48 8b 17 mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rdi]

401df3: 48 8b 47 08 mov rax,QWORD PTR [rdi+0x8]

401df7: 48 23 16 and rdx,QWORD PTR [rsi]

401dfa: 48 23 46 08 and rax,QWORD PTR [rsi+0x8]

401dfe: f3 48 0f b8 d2 popcnt rdx,rdx

401e03: f3 48 0f b8 c0 popcnt rax,rax

401e08: 48 01 d0 add rax,rdx

401e0b: 83 e0 01 and eax,0x1

401e0e: c3 ret

401e0f: 90 nop

Additionally, Yoav Ben Shalom noticed that when we get 3 bad last letters we can skip all 2^6 iterations that will yield the same letters. The gist below has been updated and now the code runs in 0.7 seconds!

The answer

Running the code yields 14 solutions that cause the program to output “Correct”. A quick check against the program confirms that they all work. Here’s the full list:

B0CFbYG14gbvA

TSG2MZ0bt3JJN

Xnu073LG6YC7q

tDDR3OA6Q7YDv

sJUA3vYTH5BI1

r2F1l2z2SyK33

4cUZ89Rti11h2

2x0LSbXAIwB84

i05SJ5E9pnl7C

R3V3s1nGkRG0G <-- Looks like t3xt

9X8LdMPGZL4Dg

0o4CaRv15p20k

V62T3zKIuDZI3

Jl2gKZf008oK6

Because we didn’t finish this challenge during the competition I can’t be completely sure but it looks like R3V3s1nGkRG0G was the solution.

You can see our code below, first the python and then the c++

comments powered by Disqus